To celebrate the Year of the Dragon, this issue of My UM features interviews with three students born in the Year of the Dragon and two professors who have researched dragon culture. While exploring the profound ethnic and cultural significance tied to being ‘descendants of the dragon’, we also take this opportunity to extend our new year wishes to members of the University of Macau (UM).

The ‘dragons’ in residential colleges

Dragon culture holds significant importance for Chinese people. To mark the Year of the Dragon, one UM residential college organised a Chinese New Year gala event for students to experience the festive atmosphere. As part of the celebration, students joined the college master and residential fellows in making dumplings. In Chinese culture, eating dumplings signifies bidding farewell to the past year and welcoming the new year. By making and enjoying dumplings shaped like ancient Chinese gold ingots, students expressed their hopes for good fortune and prosperity in the Year of the Dragon.

Among the festivities at the gala event, ‘fai chun’ writing took centre stage. Students and academic staff wrote auspicious phrases on red paper in Chinese calligraphy to express their wishes for the new year. Many of these phrases cleverly included characters with a similar sound to ‘long’ (dragon), such as ‘long (rong) guang huan fa’ (龍[容]光煥發; glow with success) and ‘guo yun chang long’ (國運昌龍[隆]; prosperity for the nation). One particular eye-catching piece was written by Martin Di Lorito, an international exchange student from Italy. With a brush pen, he wrote ‘Thank you, University of Macau’ to express his appreciation for the university’s support and guidance.

Among the students living in UM’s residential colleges, many were born in the Year of the Dragon. One such student is Zhang Haoyue. After completing her undergraduate degree in International and Public Affairs at UM, Zhang continued her studies at the university and is currently a second-year master’s student in Public Administration. She has resided in Ma Man Kei and Lo Pak Sam College since her first year at UM. As much as she enjoys her academic life here, Zhang is also enthusiastic about assisting younger students in adapting to university life. Zhang shared, ‘The college fosters a vibrant cultural ambience, especially during traditional festivals, allowing us to immerse ourselves in Chinese traditions.’

In Chinese culture, the dragon is regarded as a divine symbol, as exemplified by the ‘nine-in-the-fifth line’ hexagram in the Chinese classic Book of Changes which says ‘Flying dragon in the heavens. It furthers one to see the great man.’ In addition, the dragon represents the majesty of emperors. Zhang said, ‘Since childhood, I have been fond of dragon totems. Some historical records also mention that the Yellow Emperor himself was a dragon. As the Chinese people consider the Yellow Emperor as the common ancestor of all people of Chinese descent, we Chinese are all descendants of the dragon.’

The ‘dragon’ in Macao’s scenic spots

The significance of being descendants of the dragon extends beyond the literal meaning. The dragon embodies a vibrant humanistic spirit and has a profound influence on Macao, as reflected in the names of local places (such as ‘long song kai’ [龍嵩街]; Rua Central). Over the years, scholars from UM have conducted research on the relationship between the dragon and Macao, as well as its role in the preservation of cultural heritage. Notably, the dragon finds its embodiment in Macao’s unique blend of Chinese and Portuguese cultures, as exemplified by the Taipa Houses (龍環葡韻), one of Macao’s renowned scenic spots. The Chinese name of the Taipa Houses literally means ‘Dragon Ring Portuguese Charm’.

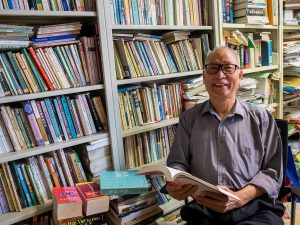

In his Chinese article (‘澳門名勝楹聯之氹仔別稱’ [The former name of Taipa Island through exploring couplets on historical buildings in Macao]) about the former name of Taipa Island, Tang Keng Pan, a retired professor from UM’s Department of Chinese Language and Literature, discusses the frequent occurrence of the name ‘Dragon Ring’ (龍環) in inscriptions and plaques found in Taipa. Examples include the inscription ‘God Bless Dragon Ring’ (福蔭龍環) on the plaque of Tin Hau Temple, the phrase ‘Chosen at the foot of Dragon Ring’ (自擇於龍環之麓) on the remaining stone tablet of Sam Po Temple, and the inscription ‘Dragon Ring Pak Tai Temple’ (龍環北帝廟) on the bronze incense burner in Pak Tai Temple. Hence, it can be inferred that ‘Dragon Ring’ was the former name of Taipa. Based on the inscriptions, Prof Tang suggests that in the past, when Macao was a small fishing village, if a boat docked at ‘Dragon Ring’ it symbolised the desire for the dragon’s protection, as well as prayers for favourable weather conditions at sea.

Today, the name ‘Dragon Ring Portuguese Charm’ perfectly captures the scenic beauty of the Portuguese-style residences along Avenida da Praia, the nearby Our Lady of Carmel Church, and the surrounding gardens. According to Prof Tang, the poetic name ‘Dragon Ring Portuguese Charm’ not only unveils the history of Taipa, but also symbolises the harmonious coexistence of Chinese and Portuguese cultures in Macao society. As the new year begins, Prof Tang extends his wishes for prosperity, peace, and continued growth for both the motherland and Macao.

The ‘dragon’ in sports

In addition to place names, dragon culture also manifests in two popular sports, dragon dance and dragon boat racing, each of which embodies the spirit of the dragon. There are two UM teams dedicated to these sports as well. Zhou Minqun, a fourth-year student majoring in Communication who was born in the Year of the Dragon, is a member of both the Macao Dragon Boat Team and the UM Dragon Boat Team. She believes that both dragon dance and dragon boat racing symbolise the profound heritage of Chinese culture. These sports not only require team members to be agile, but also to synchronise their movements and work together in perfect harmony, exemplifying the spirit of unity.

‘Amid the resounding beat of drums and the flutter of colourful flags, dragon boats race through the water as paddlers row with their oars,’ Zhou said. This captivating scene perfectly encapsulates the tradition of dragon boat culture. According to Zhou, in ancient times, the dragon was held in reverence, inspiring the creation of boats in the form of these mythical creatures. Dragon boat races were held as a way to seek blessings of good fortune and commemorate the patriotic poet Qu Yuan.

To Zhou, the dragon represents power and magnificence, while dragon boat racing signifies unity among crew members who work passionately towards a common goal. As Zhou prepares to graduate in the Year of the Dragon and pursue her dreams, she also extends her wishes for UM’s continued success. Furthermore, she hopes for good health and prosperity for her family and friends.

The global spread of dragon culture

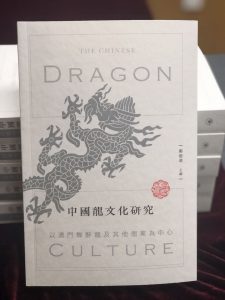

Dragon culture has evolved from ancient to modern times and extended its influence beyond China. Delving into Chinese dragon culture, the faculty and students in UM’s Department of Chinese Language and Literature researched this subject from the perspective of folklore studies and compiled their findings into a book, The Chinese Dragon Culture: Focusing on Dragon Dance in Macao and Other Cases. This significant work was published in 2019 and edited by Zheng Dehua, an emeritus professor of the department. The book explores the transformation of Chinese dragon culture from its agricultural roots to modern industrial society. In addition, it examines the spread of this culture from rural to urban settings and abroad. One particular focus of the book is the exploration of dragon dance customs in Johor Bahru, Malaysia, shedding light on the prominent international presence of dragon culture.

For Aymo Khoo, a Malaysian citizen and second-year master’s student in Financial Technology, the dragon dance procession in the temples of Johor Bahru is a familiar sight. Growing up in Malaysia, he recognised the dragon as an important cultural symbol of China. Aymo shared, ‘I was born in 2000—the Year of the Dragon. If you look at the data, there was a significant number of births in Malaysia that year, perhaps due to the auspiciousness of the Dragon Year. It made us feel special to be born in the Year of the Dragon,’ he added.

As Aymo grew older, he discovered that the dragon left its mark on many ancient civilisations worldwide, including the ‘Naga’ in Malay and Malaysian cultures. He explained, ‘In Malaysia, we call the Indian long-grain rice ‘Beras Naga’ (dragon rice) and dragon fruit ‘Buah Naga’. The festive atmosphere during the Chinese New Year in my hometown is vibrant, which I believe is comparable to that in Macao!’

Last year, Aymo and several other international students at UM went to see the dragon dance at the Ruins of St Paul’s on the first day of the Chinese New Year; they greatly enjoyed the joyful ambience. This year, Aymo returned to Malaysia to reunite with his family. He said, ‘I really miss home after a long period of studying abroad. As the Year of the Dragon starts, I wish for good health for my family and extend my wishes for success to my professors. As for me and my classmates, I hope we can make academic advancements and stay on track with our research timelines. Finally, I genuinely hope for peace in the world.’

The humanistic spirits of dragon culture

The humanistic spirits of dragon culture, which constitute its core essence, include perseverance, unity, progress, and innovation. These spirits are deeply ingrained in the Chinese people, said Tam Mei Leng, associate professor in UM’s Department of Chinese Language and Literature. Prof Tam is a key member of UM’s research team dedicated to the study of Chinese dragon culture, with a specific focus on Macao’s Festival of the Drunken Dragon. By conducting a comprehensive analysis of the festival’s evolution, she explores the transformation of the drunken dragon dance from a local activity in a small fishing village into a city-wide festival.

Through the analysis, Prof Tam discovered that Macao’s dragon culture fosters harmonious relations among neighbours and a return to simplicity and authenticity. Prof Tam explained, ‘During the festival, fishmongers and customers gather in the market, fostering a sense of closeness and solidarity. As they gather, they engage in lively conversations and share laughter. Together, they take part in a special tradition by consuming the “Dragon Boat Head Rice” (also known as longevity rice). With each bite, they hold onto hopeful prayers for longevity, prosperity, abundant wealth, and blessings of good fortune.’

According to Prof Tam, as the drunken dragon dance begins, it is evident that despite Macao’s rapid development, the community still upholds the essence of dragon culture. She elaborated, ‘Upon closer inspection, the seemingly segmented body of the dragon reveals a profound symbolism. As these segments connect and intertwine, they symbolise the interdependence between individuals and their customs, communities and industries, society and regions, and even the entire Chinese nation. I believe this spirit of unity and solidarity will endure.’

Text: Kelvin U

English translation: Bess Che

Photos: Editorial Board, with some provided by the interviewees

Source: My UM Issue 131

Students join the college master and residential fellows in making dumplings to welcome the Year of the Dragon

Martin Di Lorito gives a fai chun to Ma Man Kei and Lo Pak Sam College Master Yang Liu to show his appreciation

Zhang Haoyue

Prof Tang Keng Pan extends his wishes for prosperity, peace, and continued growth for both the motherland and Macao

UM dragon dance team

According to Zhou Minqun, dragon boat races were held as a way to seek blessings of good fortune

The Chinese Dragon Culture: Focusing on Dragon Dance in Macao and Other Cases by UM faculty and students

Aymo Khoo hopes for peace in the world

Prof Tam Mei Leng