The American poet and writer Maya Angelou once said, ‘You can’t really know where you are going until you know where you have been.’ It is important to understand and learn lessons from the past in order to avoid repeating the same mistakes in the future. This is as true for individuals as it is true for a country. To Department of History Distinguished Professor Wang Di, the relevance of studying history in the modern world is never in question. Indeed, he believes that Macao’s future prosperity depends, at least to some extent, on the quality of education in history. Driven by this belief, Prof Wang and his colleagues from the Department of History have worked tirelessly over the years to develop a quality curriculum that aims to not only improve the students’ competitiveness on the job market, but also enhance the department’s research capacity and international academic influence.

Career Options of History Graduates

According to Prof Wang, history entails training in multiple skills, which gives history graduates more career options. He says, ‘History graduates travel different career paths from pursuers of applied science. History is a branch of the humanities. With an increasing trend towards multi-disciplinary development, history now encompasses knowledge in different branches of the humanities, such as literature, sociology, political science, anthropology, and communication studies. History also demands multiple skills. Students must learn how to collect data, how to investigate, how to conduct research, and how to write reports. These skills will be very useful, whether they choose to work in the government or in the private sector. History graduates have many career options. They can work as history teachers or journalists. They can work in the government, in private companies, or in cultural institutions like museums.’ He cites his own experience to illustrate the great demand for historical knowledge, sometimes from the least expected sources. He was once invited by a casino company in Macao to teach Chinese history to its senior executives, because the company correctly reasoned that employees who understand history will provide better services to customers.

In order to create more channels for students to learn history, UM has established several research centres in recent years, including the Centre for Macau Studies, the Centre for Chinese History and Culture, and the Confucius Institute. These centres help deepen students’ understanding of the history and cultures of mainland China and Macao so they can grow into well-rounded graduates. The general education course in the civilisation of Macao and China, offered by the Department of History, is a compulsory course for all freshmen. Prof Wang explains that the department maintains a close relationship with academic research centres at UM. Many courses offered by these centres are also taught by professors from the department. ‘We plan to collaborate with these centres to launch more courses in the future, in order to help our students understand history from different angles,’ he says.

A Serendipitous Encounter with History

Born in Chengdu, Sichuan province, Wang was assigned at age 18 to do manual labour in Meishan, the hometown of the Song dynasty poet Su Dongpo. He was later transferred to a brick factory under the local Railway Bureau. His days of hard physical labour finally came to an end when he was again transferred, this time to a publicity position in the Labour Union, because of his painting skills. The poor working conditions did not dampen his enthusiasm for learning. In 1978, while still working in the Railway Bureau, he applied to the national college entrance examination. He loved painting, but he felt he was not good enough to get admitted to an art academy. So he set his eyes on art’s close cousin—literary studies, with the intention of applying to the Chinese department. But as fate would have it, he performed best in the history subject, scoring 96 points out of 100. The rest is, of course, history—he became a history major at Sichuan University.

After completing his bachelor’s and master’s degrees in the modern history of China at Sichuan University, Wang was hired by his alma mater as a teaching assistant. Two years later, at age 31, he became the youngest history scholar in China to be promoted to associate professor. In 1991, he was invited by the Committee on Scholarly Communication with China to serve as a visiting scholar at the University of Michigan’s Kenneth G Lieberthal and Richard H Rogel Center for Chinese Studies and to complete a doctoral degree at The Johns Hopkins University, under a programme for young scholars. Prior to joining UM in 2015, he was a history professor at Texas A&M University and the president of the Chinese Historians in the United States. Between 2015 and August 2018, he served as the head of the Department of History at UM.

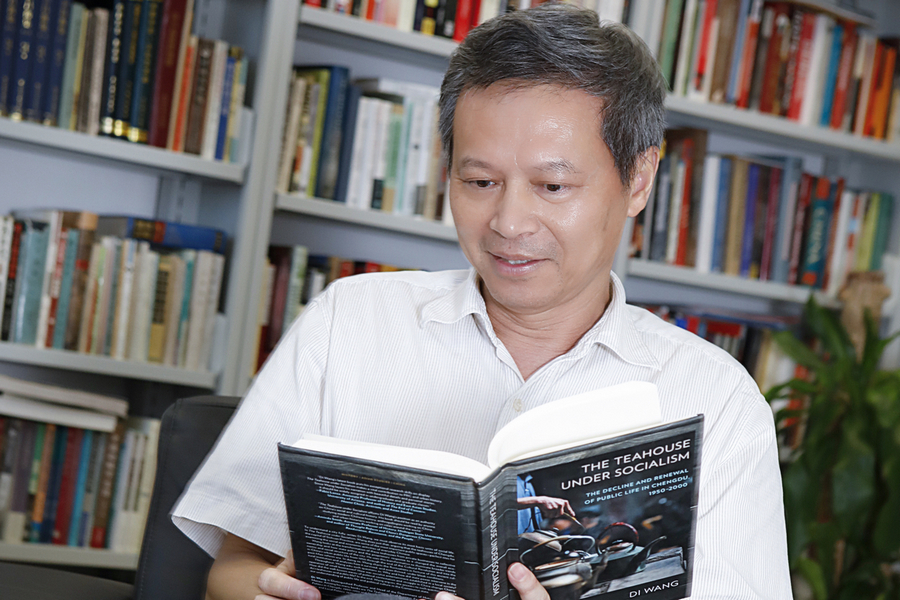

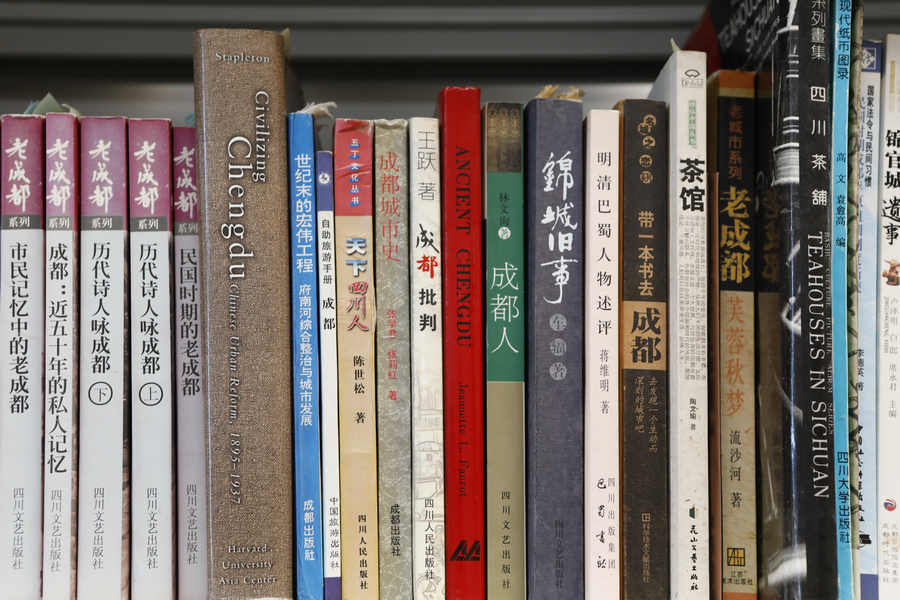

Prof Wang is recognised as one of the foremost experts on the urban history in China and new cultural history. He is the recipient of the Best Book (Non-North American) Award for 2005 from the Urban History Association in the United States and a co-editor of the English academic quarterly Frontiers of History in China. His two most recent English books, Violence and Order on the Chengdu Plain: The Story of a Secret Brotherhood in Rural China, 1939-1949, and The Teahouse under Socialism: The Decline and Renewal of Public Life in Chengdu, 1950–2000, were published by Stanford University Press and Cornell University Press, respectively. The books make a valuable contribution to existing literature on China’s contemporary history and microhistory. Based on an analysis of a large amount of documents, sociological surveys, and official and unofficial records, the books provide a thorough exploration of a secret society and teahouses in Chengdu. It is very rare for a scholar to have two monographs on history published in the same year by two of the most prestigious university presses in the United States.

Focus on Ordinary People

What sets Prof Wang apart from many historians is his focus on ordinary people, as he believes the lives of the masses provide the most faithful representation of society. He says, ‘Throughout history, ordinary people have always been in the majority. So we should understand their thoughts, activities, emotions, and experiences. It’s like what happens when you look down from a plane—you can’t see the details. But if you stand on the ground and look at the world with the eye of an ordinary person, then you can capture authentic history.’

This intensive historical investigation of a well-defined small unit of research is known as the microhistorical approach, which is characterised by a shift from grand narratives to micro-narratives. Instead of studying major political, economic, cultural, and social events, microhistory focuses on ordinary people and their everyday life experiences. Historical truths are discovered and understood through studies of seemingly insignificant objects. According to Prof Wang, microhistorical studies require an arduous journey. The fact that history is written by elites, with scarce records of ordinary people, makes the search for data seem like a literal attempt to find a needle in a haystack. It is not unusual for Prof Wang to spend weeks locating one piece of useful information and another several months to interpret the meaning. It is little wonder, then, that the book The Teahouse took him a full decade to complete.

A Clearer Perspective on the Present

In Prof Wang’s opinion, it is very important for historians to analyse data and track down their sources. He says, ‘A historian must bear in mind the subjective nature of history. Nobody can declare that the history he wrote is authentic history. The best we can do is present history as we understand it. Studying history is like travelling back and forth between the past and the present. The more you understand history, the more clearly you can see the present.’

Source: umagazine